Why Plein AIr?

by Kathleen Dunphy

WINTER'S CHILL

oil on linen

10 x 12 in

(25.4h x 30.48w cm)

$2,000

The thermometer in the car topped out at 104 degrees on the way home. I've just walked in the door after a frustrating morning out in the field and I am exhausted. I set the alarm for 4 a.m. so that I could get up and get out to my plein air destination right as the sun came up on this summer morning. But ignoring all my plans, Nature took her own course and decided to cast a few stray clouds on the horizon, just enough to obscure the sun and completely change the look of the scene I set out to paint. I tried to be patient and wait it out, but by the time the clouds passed, the sun's angle was too high for the effect I wanted to paint. And after that it was just too dang hot to stay outside any longer. Argh. It's times like this that I can't help but think about the comfort of the studio and the quick snapshot I took of the scene when I went past it last week. And the question that so many people ask me: Why plein air? Why not stay in the studio and use those great photos you took? Why haul all your gear out there and stand in the heat/cold/wind/bugs just to do a little painting you could whip out in your climate-controlled studio in no time?

The answer is simple: no painting done from a photo can ever compare to the energy, immediacy, and sense of place that can come through in a plein air piece. Somehow the feel of the day, be it heat or cold or wind or just a perfectly pleasant morning, makes its way down the arm and off the brush and onto the canvas. I wish I knew how it happens so I could fake that quality in the studio, but that's the magic of plein air. Our experience comes out on the canvas. All our senses help to create the painting, not just our vision. We hear the cows lowing, we feel the breeze, we smell the hay.....it's all there on the canvas. Even my worst plein air pieces have some small element of that particular day in them. I feel like I'm recording a moment in history: it will never be July 28, 2011 at 6:00 in the morning ever again in the history of the world, but now I have a little bit of it on canvas. How exciting is that?

Not all of my paintings are completed on location, and I paint many larger works entirely in the studio. But every piece I paint has its genesis in plein air studies. Working solely from photos leaves my paintings looking flat and unexciting. I use my reference photos to jog my memory or to help me come up with better designs that I may have overlooked when I was on location. But I can't tell you how many times I've discarded a studio painting because I didn't have enough plein air information on the scene to make the painting look convincing and alive. All the answers are outside, and even the most frustrating day of plein airing brings a more acute awareness of the subtleties of painting from life. Those skills honed outside make the studio work that much easier and fun.

So now it's 2 days since I wrote that opening paragraph, and what did I do? I went out the next morning and hit it again...driving to that same spot and waiting for the sun. And this time it was perfect--all the things I love about painting outside all came together in a couple of magic hours. I painted two quick studies for a larger studio piece I have rattling around in my head, then rewarded myself with a loose, just-for-the-heck-of-it study on the way home. Standing in the shade of an oak tree with my dogs lounging around my feet, painting blooming oleander and distant hills with no expectations in mind except for the fun of putting paint on canvas: that's just about as good as it gets. And that's why I plein air.

click to view works by Kathleen Dunphy

________________________________________________________________________

Composition II

DIRECTING THE EYE

Robert Moore, 2015

IN THE GARDEN

oil on canvas

40 x 30 in

(101.6h x 76.2w cm)

$9,000

"Composition is directing and maintaining the gaze of the viewer. It is like putting down several visual magnets within an area, drawing the eye here, countering that shape, repelling the eye there, allowing passage, or arresting the viewer's gaze. It is controlling how your viewer's eye moves through your painting. The eye will go to where there are contrasts. There are many qualities in which there can be contrasts e.g. light vs. dark, intense vs. dull, hard vs. soft, straight vs. curved, organic vs. geometric, etc.

Every mark you put on the canvas, every space, every shape that you are creating is going to effect the viewer's gaze. If there is high contrast in an area then you want to make sure the information is both clear and interesting. It is like someone who yells in a library, if they are communicating that there is a fire you are fine with the audible contrast but if they are talking about what they are having for lunch it is not desirable."

click to view works by Robert Moore

________________________________________________________________________

The Science of Responding to a Painting

Jenness Cortez, April 2015

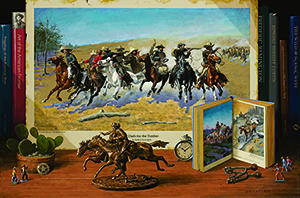

THE LEGEND MAKERS

acrylic on mahogany panel

24 x 36 in

(60.96h x 91.44w cm)

What makes us give our attention to a painting? What makes exploring it a pleasure? Let’s look at the science.

We human beings have brains that consist of two halves, each with different functions. The right brain thinks in holistic pictures and is the source of intuition, and the left brain organizes, categorizes, retrieves memories and employs logic. Together the two halves create our experience of the world.

When we look at a realist painting we first respond to light and color, then to a general recognition of the visual imagery; we see a horse or a landscape, for instance, that’s our right brain at work. Then we start processing the details (what kind of horse; which landscape), as well as the memories and emotions those details trigger. That’s the left brain’s contribution.

All that can happen quickly. But what makes us want to linger and enjoy the picture? It seems that both brains must find reward in the explorations. That’s why my paintings strive first to be beautiful, but always give the left brain an intriguing storyline to consider.

click to view

________________________________________________________________________

The Foundation of a Painting

Robert Moore, 2015

Jubilee

oil on canvas

40 x 40 in

(101.6h x 101.6w cm)

$10,800

My goal in this painting is to achieve a dynamic balance of harmony with variety. The harmonies will be from a common denominator of color which makes the forms feel bathed by a common light source. The variety in the painting will come from a natural progression, a changing of hue, value, and intensity in each of the masses which make up the painting. There will also be a major-minor relationship between many other aspects of the painting. For instance, the painting will be major dark minor light. There are also many other contrasts in the painting that will contribute to the variety. The mature aspens are juxtaposed against the fledgling trees and the dark pines becomes a stage for the lighter mass of the tree trunks and the intense foliage. As I create a few simple dynamic linked shapes which are unequal in mass, fill them with harmonious color, give the eye a small amount of detail to suggest a center of interest, I will produce a pleasing composition. Robert Moore

click to view

________________________________________________________________________

Stay in Control of Your Composition!

Robert Moore, 2015

WINTER'S VIRTUE

oil on canvas

60 x 48 in

(152.4h x 121.92w cm)

"Stay in control of your composition, don’t just paint things the way you see them. You are the creator, you are in charge, and the references from nature are just tools. They are just files from which you can pull shapes, colors and relationships. The end product is your canvas. Apply what you know to make your painting better and exaggerate the depth and beautiful relationships, or get a post-it note and stick it on your painting that says, “I know my painting is boring, monotonous, and flat but it really looked that way.” It's your choice. I encourage you to be in control and not say, "That's the way it really looked."

Don't worry about style, style will take care of itself. You don't have to try to be different, you are different. Just be yourself and put things down the way you would put them down expressing the unique treasure that is you. No one else can do it the way you do it." Robert Moore, March 30, 2015

click to view

________________________________________________________________________

Communicating Through Art

Jenness Cortez, March 2015

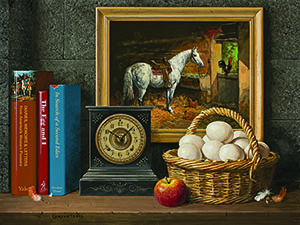

COUNTRY MORNING

acrylic on mahogany panel

15 x 20 in

(38.1h x 50.8w cm)

"Painting is my way to communicate the meaningful, the beautiful and the amazing things I see. For as long as I can remember, I’ve wanted to share through art – whether it’s something as simple as the way sunlight warms the corner of a room or as complex as the story of how a Native tribe lost its way of life. The passion I feel when my eye sees how the story can be told in images is a great motivation. I want to tug at your sleeve, point and say, “Look, look! Let me show you the wonder of it!” Jenness Cortez, 2015

click to view

________________________________________________________________________

A Progression of a Painting

William Whitaker, March 2015

GLIDE

oil on panel

16 x 12 in

(40.64h x 30.48w cm)

We are pleased to share with you the comments and images of the progression of a painting by William Whitaker that is featured in our Essence of the Human Form Exhibition in our Scottsdale gallery.

"I’m particularly proud of this little painting. It’s stylistically pretty sophisticated and rather different from most contemporary gallery painting.

Until about the mid 1920’s, white lead was the ONLY white paint available to artists. It was the white used by all the Old Masters, the white you see in all the paintings in museums. It is semi-opaque and as it ages and cures, it becomes both more luminous and more translucent. If the ground the work is painted on is a brilliant white, the painting will only get better with age. Many of the Old Masters paintings were executed on toned surfaces – mid grey-brown surfaces. As the paint on top aged, the white lead contend became more transparent allowing the dark underpainting color to influence the top layers. Hence, many of the old canvases are considerably darker now than they were when originally finished. The MONA LISA comes to mind, as do the works of Titian."

My painting will stay bright and will look better and better with age. William Whitaker, 2015

click to view progression

________________________________________________________________________

Clear Information in Painting

Robert Moore, January 2015

WINTER'S VOICE

oil on canvas

36 x 48 in

(91.4h x 121.9w cm)

"I want to clearly communicate a sense of space and order on my canvas. The snow will clearly be a separate mass, the water will be a separate mass, along with the foreground trees and background trees. I want the viewer to know what he is looking at. For it not to look 'cut-out' there has to be lost and found transition areas between those masses and variation of value, hue, and intensity within. The challenge is to keep clarity and separation without it being monotonous. There is a tendency to focus on the differences within the masses and reach for a value that belongs to the range of the neighboring mass. For example, if I see a darker value in the snow and reach for a value that belongs to the tree mass without remembering the overall relationships I will lose the order and the clarity that is reflective of nature. Once in control of the masses and their values it is time to apply ordered color." Robert Moore, 2015

________________________________________________________________________

Separations of the Value Masses

Robert Moore, October 2014

OCTOBER'S VOICE

oil on canvas

70 x 96 in

(177.8h x 243.8w cm)

"In Nature there will always be variations of values within the light masses and within the dark masses. The challenge is to see these variations within the context of the whole. The darker lights must still belong to or relate to the light family. The lighter darks must still belong to the dark family. The darkest light will always be lighter than the lightest dark and the lightest dark will always be darker than the darkest light. If you are only focused on the light mass and forget to keep it in context with the darks you are prone to paint the light variations too dark. Another way to understand this is to think of a first grade classroom and a tenth grade classroom. The tallest first grader will always be shorter than the shortest tenth grader and the shortest tenth grader will always be taller than the tallest first grader. When we deal with values we have to be aware of all of the masses and maintain a clear separation between the masses of light, the masses of medium, and the masses of dark."

________________________________________________________________________

Exaggerating the Truth When Painting Color.

Robert Moore, October, 2014

AUGUST HARVEST

oil on canvas

36 x 48 in

(91.4h x 121.9w cm)

"Most people would look at the sky and paint it blue, one hue, one value, one intensity. Maybe the small section of the sky you are painting would look like that, but if you look from the horizon to the zenith you can see a progression of color going from warmer to cooler, lighter to darker. If you look from side to side you will also see a transition toward or away from the influence of the sun. A painting will be more enjoyable and true if you take the information, the order present in the whole sky, compress it and apply it to the section of the sky you are painting. When the order of the color is exaggerated it will feel more 'true' than if you merely replicate the small section of sky that is in your composition."

click to view works by Robert Moore